Ongoing studies on instrument aerosols provide preliminary safety guidelines for band classrooms and ensembles.

If school districts didn’t have meaningful scientific data on best practices for mitigating the spread of COVID-19 in music rooms before the start of the 2020-2021 school year, Dr. Mark Spede—president of the College Band Directors National Association (CBDNA)—feared that many performing arts programs would be in jeopardy. Dr. James Weaver, director of performing arts and sports at the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS), shared Spede’s concern.

“In a normal, non-pandemic year, the arts programs are some of the first to get budget cuts,” Weaver says. “We wanted the real answers.”

“In a normal, non-pandemic year, the arts programs are some of the first to get budget cuts,” Weaver says. “We wanted the real answers.”

Spede and Weaver are getting those answers from ongoing studies that are measuring the aerosols emitted by band, choir, and theater performers. On behalf of their organizations, they are chairing the International Coalition of Performing Arts Aerosol Study, a collaboration between the University of Colorado Boulder and the University of Maryland and commissioned by more than 125 performing arts organizations.

“We [are] trying to save music,” says Spede, who is also director of bands at Clemson University. “People are still operating under fear and ignorance rather than looking at the science.”

A separate study, Bioaerosol Emissions and Exposures in the Performing Arts: A Scientific Roadmap for a Safer Return from COVID19, is being conducted by researchers at Colorado State University (CSU) with The American Bandmasters Association Foundation, National Band Association, and other groups as lead supporters.

Cover Your Face and Instrument

Cover Your Face and Instrument

Dr. Rebecca Phillips, director of bands at Colorado State University and the president of the National Band Association, says the study at Colorado State is looking at large numbers of musicians, singers, and dancers while the Performing Arts Aerosol study is looking at multiple routines for one musician. Researchers in the CSU study are gathering data from 10 flute players, for example, and analyzing that data to determine the range of aerosols emitted across those 10 players.

The study found that different instruments varied in aerosol release, ranging from flute/piccolo with the least particle emissions to trumpet, saxophone, and bassoon with the highest emissions. French horn and oboe fell into the moderate range. However, variability also occurred among individuals.

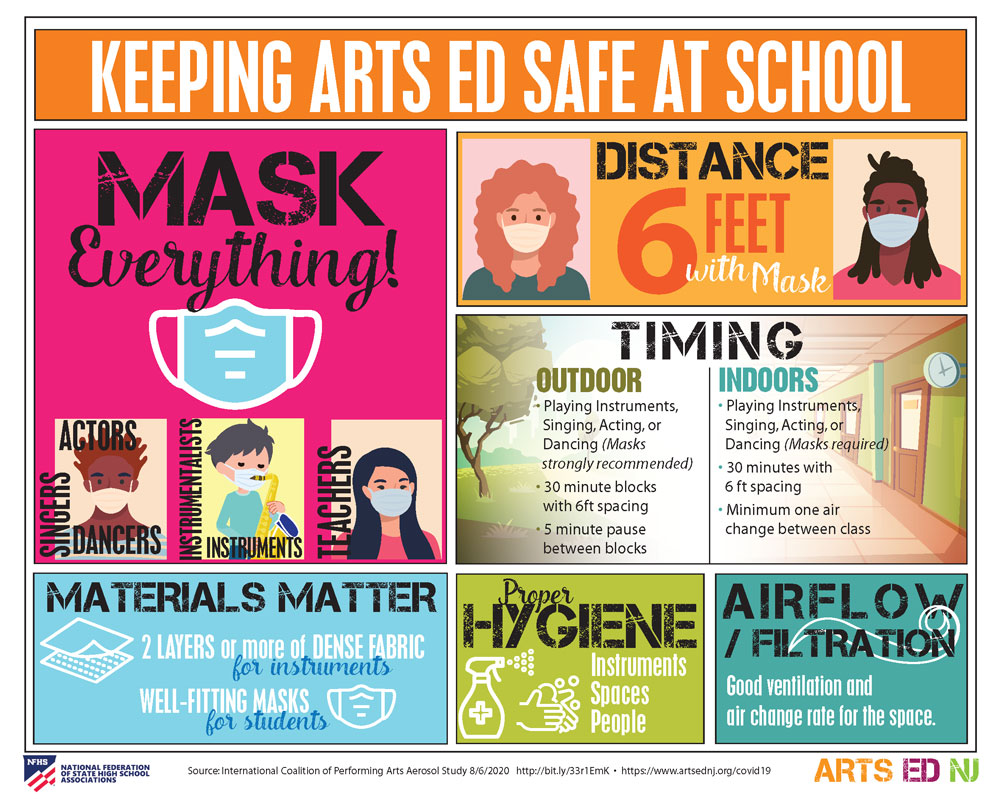

The Performing Arts Aerosol Study analyzed the concentration and pathways of airborne particles over time with and without masks and instrument covers. The study found that instruments like trumpet and clarinet, with straight shapes from mouthpiece to bell, had higher aerosol concentrations. The findings also suggest that most wind and all brass musicians should wear a mask with a small horizontal slit for their mouthpieces while performing and rehearsing. Flute players should wear masks without slits and slide the flute behind their mask from the side to access the embouchure hole. Some directors are implementing the use of face shields for flutists.

If students are not masked while they are playing, researchers are advising band directors to space their students 12 feet apart. If musicians are masked, the typical 6 feet works fine except for trombone players, who need 9 feet of space due to the extension of the instrument and slide.

The study also recommends that players equip their brass and woodwind instruments with bell covers. “You have different types of covers, but I think all of those will produce similar results within a certain range,” says Dr. Jelena Srebric of the University of Maryland and one of two lead researchers on the Performing Arts Aerosol study.

Ideally, bell covers should be made of non-stretchy material that has a Minimum Efficiency Reporting Value (MERV) of 13, known to protect against sneezes and coughs.

Unlike brass instruments, woodwinds produce aerosols that stream from their bells as well as their keys. “How much, we don’t exactly know yet,” Spede says. Researchers have been experimenting with woodwind bags and socks, but “if the aerosols that are produced from keys are negligible, it might not be an issue,” Spede adds.

Students and band directors who are handy with a sewing machine may want to visit the United Sound website, which provides patterns for two kinds of overlapping masks and wind instrument bags in a variety of sizes.

Various uniform, instrument, and marching accessory companies are also offering their own brands of musicians’ masks, bell covers, and bags.

Clear the Air

Playing instruments outdoors is considered a best practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. When students must play indoors, however, band directors should be mindful of the airflow within their classrooms. In general, the standard air change rate in a typical classroom is three air changes per hour. In other words, the air changes in a room completely every 20 minutes and naturally removes aerosols as it does.

Researchers from the Performing Arts Aerosol Study recommend that band students play their instruments together while indoors for no more than 30 minutes, using mitigations like social distancing, masking, and bell covers. After 30 minutes, the room needs to be cleared and unoccupied for 20 minutes to allow the heating, ventilation, and air conditioning system to perform an entire air change before allowing a new set of students into the room. However, researchers cannot predict the airflow in a given room. For example, if a student has COVID-19 and is seated near a vent that is blowing fresh air, that air could carry the student’s aerosols to others.

To further improve air change rates, band directors whose rooms are equipped with windows should leave them open, preferably with a running box fan. Srebric suggests orienting the fan, so that it is supplying the room with fresh air.

“If you are exhausting [the air], you are drawing air from other parts of the building into the classroom, so you have the opposite effect of what you’re trying to achieve,” she says.

Before band directors welcome their ensembles into their band rooms, they should measure their rooms for social distancing requirements, create a template, and clearly mark spaces on the floor. Arranging students in rows will allow for more space between each student while also preventing aerosols from streaming directly into students’ faces when seated in arcs. To limit the number of students per ensemble, band directors should create a rotating timed schedule with more sections if the master plan allows.

Avoid Shared Equipment and Spaces

Although seemingly common sense, the Performing Arts Aerosol Study cautions against sharing instruments. If students must share, the instruments should undergo a thorough cleaning between players. Percussion students should not share mallets without disinfecting them or wearing gloves. Students should receive personal music kits that include common classroom instruments, rhythm sticks, mallets, etc. Music directors who teach the recorder should supply one for each student.

Students playing brass instruments should not empty their spit valves on the floor. The study recommends that music directors supply brass players with puppy wee wee pads to catch the contents of spit valves.

To dissuade students from congregating in close quarters, band directors must limit the number of students accessing instrument storage rooms. Instruments should not be stored in a common area in the classroom. Antiseptic wipes that contain at least 70% alcohol should be available to students in the classroom, or students should bring their own. Students can be responsible for wiping all surfaces before and after touching them.

Weaver calls music educators problem solvers, a personality trait that serves them well when confronted by challenges like the COVID-19 pandemic. Those who innovate, use creativity, and focus on what they can do rather than what they can’t will overcome this year’s obstacles, he says.

The Performing Arts Aerosol Study is critically important and has provided band and chorus directors with the data they need to “get their bands and choirs in session,” Weaver says.

As a whole, the various aerosol studies are relevant today but will also serve educators well into the future, helping them mitigate the spread of other respiratory diseases. “These mitigation strategies should be incorporated for the long term to keep our students healthy in the foreseeable future,” Weaver says. “We’re working around the clock with as many national organizations as possible to provide as many recourses that teachers can use to make music as important today as it was yesterday and to keep it important.”

COVID-19 should not be feared, but it must be respected, Srebric says. She advises individuals to refrain from engaging in risky behavior and respect individuals in their community by practicing mitigations suggested by the healthcare community. “If we take it not as a torture that was unfairly brought upon us but as a challenge that we are all facing together, even very [young kids] can learn a form of discipline,” Srebric says. “This will make them much more powerful adults.”