The CBDNA Intercollegiate Marching Band unified performers in a virtual show for the College Football Playoff National Championship game as well as on more personal, deeper levels.

Marching band members at Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana, have long anticipated a bowl game performance. Though they could not accompany the football team to the Arizona Bowl—the school’s first bowl game in nearly seven years and first-ever bowl win—on Dec. 31,  2020, two of its members still had a bowl game performance through the College Band Directors National Association (CBDNA) Intercollegiate Marching Band (IMB). According to Caroline Hand, director of athletic bands at Ball State, she and her students are grateful for “getting the opportunity to do the Intercollegiate Marching Band since they had to miss the bowl performance.”

2020, two of its members still had a bowl game performance through the College Band Directors National Association (CBDNA) Intercollegiate Marching Band (IMB). According to Caroline Hand, director of athletic bands at Ball State, she and her students are grateful for “getting the opportunity to do the Intercollegiate Marching Band since they had to miss the bowl performance.”

The CBDNA IMB, presented by GPG Music and Our Virtual Ensemble in partnership with Halftime Magazine, Guard Closet, StylePlus, and CollegeMarching.com combined nearly 1,500 nominated performers from almost 200 college marching bands in 45 states and Puerto Rico. Yamaha Corporation of America, DeMoulin Bros. and Co., Cousin’s Concert Attire, FlipFolder, FansRaise, and Tresona also supported the endeavor.

The band’s premiere performance occurred virtually during halftime of the College Football Playoff National Championship game on Jan. 11, 2021. The show aired simultaneously on video screens at Hard Rock Stadium in Miami Gardens, Florida, and on the IMB YouTube channel. “I had high expectations when the project was first mentioned to me last fall [by CBDNA], and … the students have exceeded them!” says Bill Hancock, executive director of the College Football Playoff. “This makes me want to pull out my clarinet and go eight-to-five again.”

Unity and Visibility

All marching bands experienced an unusual season in 2020. Some college ensembles played in the stands at games while some couldn’t step foot in the stadium at all.

Other bands had their seasons canceled entirely. “A variety of programs have been sidelined due to COVID,” says Barry Houser, chair of the CBDNA Athletic Band Committee and director of athletic bands at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “[The IMB] is an opportunity for our students … to participate in something marching-band-esque on a national scale.”

CBDNA sought to create a post-season bowl game performance that many bands were denied in 2020. According to Houser, the IMB had two main goals: “to unify college band programs throughout the country” and “to make sure college bands were still visible.”

As the director of a Big 10 band, Houser appreciated the performance opportunities for his students. “The Big 10 Conference did not allow fans, bands, or dance teams to be a part of the season this fall,” he says. “We were primarily confined to Zoom rehearsals. The IMB provided a chance to perform again, the ability to practice and work toward a goal.”

For the combined performance, the IMB played Beyonce’s 2011 hit song “End of Time.” Scott Boerma, director of bands at Western Michigan University, and Chuck Ricotta, the percussion instructor/arranger for the University of Michigan Marching Band, created the marching band arrangement for the IMB.

Houser cites the “natural marching band sound” in “End of Time” as a reason for selecting the song. “First, there were some ideas about [performing] something patriotic in nature,” Houser says. “We wanted to do something different, something that was going to spotlight one of the great artists of today’s time.”

Color guard and dance team members received 10 to 15 seconds of choreography designed by Michael Rosales, lead choreographer for Santa Clara Vanguard Drum and Bugle Corps, while twirlers and majorettes performed segments designed by Lexi Duda, a national and World Champion twirler previously with the University of Maryland. Dissecting the choreography into shortened segments helped highlight the different styles of schools across the country and streamlined the video editing process.

Each band could nominate up to five musical performers, including winds, brass, and percussion, as well as five auxiliary performers, including guard, dance team, drum majors, and twirlers, to participate in the IMB.

Behind-the-Scenes Logistics

Compiling a performance with nearly 1,500 members required some logistical planning. IMB producers suggested that students wear uniforms to showcase their school colors, creating a unique but worthwhile challenge for band directors. “We had not checked out uniforms this year because we’d have to be gathered inside,” Hand says. Nominated students from Ball State retrieved their uniforms “one at a time with a staff member who was also masked.”

At Northwestern State University in Natchitoches, Louisiana, members of the Tau Beta Sigma band sorority set up a series of pickup times for students to safely retrieve their uniforms.

For recording their individual parts, students and bands also needed to problem-solve. “Some did it in their apartment or dorm; some did it out on the practice field with a video or phone,” says Daniel McDonald, assistant director of bands at Northwestern State.

Students found a plethora of interesting places to record. “My band director takes up photography and videography as a hobby; he let everyone who was recording instrumental parts [go] to the band room, where he had a black backdrop for his photography,” says Carl Walden, a trumpet player from the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “We had a laptop [set] up to the side and had headphones behind us.”

Students found a plethora of interesting places to record. “My band director takes up photography and videography as a hobby; he let everyone who was recording instrumental parts [go] to the band room, where he had a black backdrop for his photography,” says Carl Walden, a trumpet player from the University of Alabama at Birmingham. “We had a laptop [set] up to the side and had headphones behind us.”

Some bands allowed students to record in their stadiums. Hadley Deputy, a color guard member from Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia, went to the stadium with a music stand, a camera, and a laptop. “My boyfriend would start the camera [and] push play on the computer [with] the audio,” Deputy says. “It took three hours to film it all.”

Other students had to record from home. “For the video, I did the rifle work. I went outside in my backyard and set up a camera,” says Maeve St.Onge, a color guard member from Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut.

Students submitted their videos using Our Virtual Ensemble, a program created by GPG Music. The program walked students through the process of recording. “They make the recording to a video of a conductor, which has a backing track with a metronome click,” says Steve Martin, owner and chief executive officer of GPG Music. “It’s almost like being in the recording studio.”

Students submitted their videos using Our Virtual Ensemble, a program created by GPG Music. The program walked students through the process of recording. “They make the recording to a video of a conductor, which has a backing track with a metronome click,” says Steve Martin, owner and chief executive officer of GPG Music. “It’s almost like being in the recording studio.”

Hours and Hours of Clips

Through Our Virtual Ensemble, Martin had edited many virtual performances before; however, he says IMB was 10 times bigger than most of his other projects. “Normally we work with … maybe 50 [to] 120 videos,” Martin says.

One of Martin’s goals during editing was to keep the spotlight on the students themselves rather than on special effects or graphics. “Our goal was to show as many people’s faces as much as possible,” Martin says.

Martin used Adobe Premiere to edit the video clips. “When the students create the videos, … there’s dead space” based on when students start playing after pressing record, Martin explains. “We line up the videos horizontally. … Then we start pulling the audio out separately and send it to the sound engineer to balance things.”

Martin used Adobe Premiere to edit the video clips. “When the students create the videos, … there’s dead space” based on when students start playing after pressing record, Martin explains. “We line up the videos horizontally. … Then we start pulling the audio out separately and send it to the sound engineer to balance things.”

Martin hired John Meehan, brass caption head for the Blue Devils, as the project’s audio engineer. Meehan edited the audio in Logic.

Three editors worked on the video during a span of more than two weeks. Martin says that he spent about 60 hours editing the video while his other team members spent at least 70 hours each.

Some students also helped in the video editing process. Hannah Butler, a trumpet player for the University of Northern Iowa in Cedar Falls, worked on the video introduction and the outro credits. “I worked with Florida A&M University [FAMU] to get footage of their drum major doing a field entry,” Butler says. “[We edited] it together to have a virtual field entry to start the show.”

Deputy also helped organize the credits in her role as student logistics team lead. “We went through a list of the [registrations] and cross-referenced them with the video submissions,” Deputy says. “I had to type up a really long list of people to send over to the video editors to make sure they [got] it all in the credits.”

Deputy also helped organize the credits in her role as student logistics team lead. “We went through a list of the [registrations] and cross-referenced them with the video submissions,” Deputy says. “I had to type up a really long list of people to send over to the video editors to make sure they [got] it all in the credits.”

More Than Just One Show

The IMB is not only about one halftime performance; the organization also built a band community online. “The halftime performance is the shining star to say, ‘We’re here,’ and everything that follows is going to be much bigger,” says Walden, who also worked as the student programming lead for the IMB.

Walden’s work included planning a pregame livestream before the official video debut as well as organizing a series of roundtable discussions. After the initial halftime performance, the IMB released the roundtable interviews, one per day for several weeks, on its YouTube channel. “We discussed band traditions, how COVID affected [their] season, [and] tips and advice for high schoolers wanting to audition up to the college level,” Walden says. “There’s some really good information I wish I had coming into college.”

To promote the big halftime performance and all of IMB’s new video content, social media teams worked to build up IMB’s Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube pages. As the student spotlight leader, St.Onge produced social media graphics highlighting individual students from each participating school. Deputy, who also works on the student public relations team, emailed each band director with a customizable press release, photos of their students, and social media graphics.

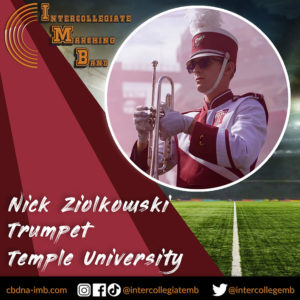

A student team also created the IMB website at cbdna-imb.com. Nicholas Ziolkowski, a trumpet player for Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and the student leader for the web development team, worked with Deputy and two other students to showcase the IMB’s bands, sponsors, videos, and performance information on the site. “I am a management information systems major,” Ziolkowski says. “This was an opportunity to have a real-life project that could possibly have a huge impact on an organization as well as this upcoming community.”

A student team also created the IMB website at cbdna-imb.com. Nicholas Ziolkowski, a trumpet player for Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and the student leader for the web development team, worked with Deputy and two other students to showcase the IMB’s bands, sponsors, videos, and performance information on the site. “I am a management information systems major,” Ziolkowski says. “This was an opportunity to have a real-life project that could possibly have a huge impact on an organization as well as this upcoming community.”

One Big Community

As a byproduct of these student-led teams, performers across the country formed close relationships with one another and worked closely with IMB founding partners. “Not only do you get to work with people who are knowledgeable in their field, [but] it’s also cool to meet people across the country,” Walden says. “I’ve already made friends with the FAMU drum major.”

Multiple student leaders say that they were glad to make industry connections and gain on-the-job experience. “Speaking as student spotlight leader, I’m getting connected with so many industry professionals,” St.Onge says.

Deputy echoes the sentiment. “My major is graphic design, and I want to get into advertising in the future,” she says. “I figured this [experience] would help with skills, … especially with designing a website.”

Even outside of teams and leadership positions, IMB members have formed friendships through full-band Zoom calls. “We’ve gotten to do breakout rooms and go to our instrument groups,” Butler says. “I got to meet trumpets from all over the U.S. We were talking like old friends and getting to know each other. Even though we go to different schools and have different experiences, we’re all one big band community.”

These Zoom calls provided students with a much-needed sense of community. “I didn’t realize how involved, how elaborate [the IMB] was going to be, how much more than submitting a recording it would be for these students,” says Casey Goodwin, director of athletic bands at the University of New Hampshire in Durham. “They’ve been meeting on Zoom. There’s been more interaction. They’ve been having fun doing this.”

Band directors, especially those outside of Division 1 schools, have enjoyed getting to work on a large-scale national performance. “Our students don’t necessarily get all those big D1 opportunities yet since we’re just now transitioning in,” says Dr. Gary Westbrook, director of athletic bands at Tarleton State University in Stephenville, Texas. “For our students to get an opportunity to participate in a virtual performance at the national championship, we’re gonna do it!”

While the pandemic has been a dark storm cloud over the marching band season, the IMB has been somewhat of a silver lining. “COVID has [not] been a positive thing, but … we’ve reimagined what we can do,” Houser says. “We’ve been able to pull 200 programs together in a performance that’s going to unify almost 1,500 college students.