Shore up your marching program to avoid and recover from common money problems.

Operating a marching arts organization, whether independently or as part of a high school or college, can be an expensive endeavor. As any leader knows, there are good years and not-so-good ones.

David Hobart, executive director of the Sunrisers Drum and Bugle Corps on Long Island, New York, knows all about the highs and lows. This winter, the Sunrisers’ 2020 season got off to a slow start. Membership numbers were down, and fewer members mean less paid tuition. Hobart found a way to increase signups by calling prospective members himself.

Financial pitfalls and challenges have sent marching arts performance groups into countless crises over the years. Some scale back or shut down; others move forward with solutions that fill up their coffers or, at least, keep the uniforms and instruments in relatively good shape.

“The Sunrisers through the years have had many ups and downs,” says Hobart of the all-age competitive corps that began in 1953. “The thing is: How quickly do you get up and dust yourself off when you’re down? … My advice to any ensemble director is just never give up.”

Create a Rainy-Day Fund

Not-for-profits operate close to their margins, a dangerous business model that leaves them vulnerable to emergencies. But marching arts performance groups, in particular, can run on even thinner margins, relying primarily on dues and scattered donations, says Rick Cohen, spokesperson for the National Council of Nonprofits. “Any unexpected expense can really throw the group for a loop,” he says.

School budget cuts and inadequate budgeting, planning, and saving are common financial challenges for groups.

“The biggest thing where people fail is they don’t budget properly,” says Scott McCormick, founder of the National Association of Music Parents, which supports parent music booster organizations. “Every organization needs to have a realistic budget that deals with not only the knowns but also some of the unknowns.”

A budget doesn’t need to be sophisticated, says Dr. Sarah Nathan, associate director of The Fund Raising School at the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy at Indiana University – Purdue University Indianapolis.

If you don’t feel comfortable with your own money management skills, get support. “The key is to find people who can help with that, so that you have a really strong understanding of how you’re spending your money every year and what those revenue sources are,” Nathan says.

Avoid the mentality of keeping up with the Joneses. Despite being low on funds, some ensembles purchase the latest uniforms or invest in new instruments to match the flashier equipment and costuming of their wealthier competitors.

“It probably happens way too much,” McCormick says. “We’ve all been our own worst enemy in this profession.”

Build up a reserve that’s in a separate account from your operating funds to help pay for the next time the sound system crashes or the equipment truck breaks down.

Just raising dues by $5 per person per year with the intent that the money gets shuttled into a rainy-day fund can help, Cohen says. It takes time, but that’s OK. “Over a few years, that will build up without being a significant barrier,” he says.

Prioritize Communication and Continuity

Planning poorly for emergencies isn’t the only hazard. Frequent leadership changes in boards or booster groups might result in a lack of consistency. Communication issues between staff and volunteers can result in misunderstandings, especially during a crisis.

“From a parent booster organization perspective, the times that I’ve seen parent organizations and teachers or directors come at odds is when there’s just a blanket expectation that needs are going to be met regardless of whether it was budgeted for or not,” McCormick says.

Band directors and fundraising leaders should meet face-to-face every other week to stay on top of needs and issues, McCormick recommends. The regular dialogue helps groups map out plans for specific needs and ensures everybody is on the same page if disaster strikes.

“If the expectation is that the money is going to come from a parent or booster organization, the director needs to be clear about what the expectation is,” McCormick says.

To ensure consistency as board members cycle in and out, Nathan advises groups to improve continuity through staggered terms and mentorship of new members before old chairpeople move out.

“Make sure that the baton is passed on in a way that sets up the next group of parents and the next group of volunteers to be really successful, so they’re not starting from ground zero,” Nathan says.

Reconsider Your Fundraisers

Ineffective fundraising efforts—and inaction about them—can also drag down a group. In the 1980s and 1990s, Bingo nights brought in hundreds of thousands—even millions—of dollars.

But people don’t play bingo like they once did. And when some organizations failed to find a modern alternative, they folded.

Not-for-profits can be slow to move on to new money-raising tactics when a longtime favorite is no longer successful. “They get stuck,” Nathan says.

Relying on a single event, like those Bingo nights, is risky, Nathan says. Event planning can take a lot of time, and people’s interests change. If the event or activity fails, disaster can befall an organization that has no alternative plan. Diverse donor pools and revenue streams are key, Nathan says.

But bands also should be strategic, McCormick recommends. “All too often, I see these programs that will do eight or 12 fundraisers a year, and they’re nickel-and-diming their communities by selling candy and candles,” he says.

Especially when facing high-cost needs or emergencies, creative efforts may be your best recovery plan.

When Dabni McCrary saw the aging percussion equipment used by her son at Fletcher High School in Neptune Beach, Florida, she sprang into action. Through a GoFundMe online fundraising page and other efforts, she raised $15,000 within a month to replace the equipment.

When Dabni McCrary saw the aging percussion equipment used by her son at Fletcher High School in Neptune Beach, Florida, she sprang into action. Through a GoFundMe online fundraising page and other efforts, she raised $15,000 within a month to replace the equipment.

The effort forced McCrary to get out of her comfort zone and be vocal about what the band needed. “I had to be willing to tell the community the story of what we needed and why it’s important and share lots of media and videos and pictures of the kids using this stuff and show them that it’s broken,” she says. “If people don’t know, they won’t help.”

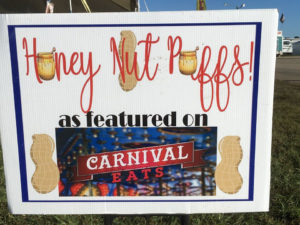

The Headland (Alabama) Middle and High School can thank a carnival delicacy and an instrument drive for helping to shore up the program.

A few years ago, a band parent came up with a recipe for Honey Nut Puffs, a deep-fried peanut butter and honey treat, to sell at the band’s longtime concession stand at the National Peanut Festival in Dothan, Alabama. Coupled with a move to the festival’s main food area, Honey Nut Puffs have doubled the stand’s profits, and the snack was featured on the Cooking Channel show “Carnival Eats.”

A few years ago, a band parent came up with a recipe for Honey Nut Puffs, a deep-fried peanut butter and honey treat, to sell at the band’s longtime concession stand at the National Peanut Festival in Dothan, Alabama. Coupled with a move to the festival’s main food area, Honey Nut Puffs have doubled the stand’s profits, and the snack was featured on the Cooking Channel show “Carnival Eats.”

On a smaller scale in summer 2018, the band set up a community instrument drive that netted local media coverage. The drive brought in 25 instruments, and additional drives will be planned.

“There are a lot of programs out there struggling, and we’ve just tried to be creative,” says John Taylor, Headland band director. “The more people you can get involved with your band, parents, and community, then I think the more they’re willing to help out. Sometimes that doesn’t come in money. Sometimes it might come in somebody’s old, used instrument that still can be played.”

Promote the Good and Band Together

Bands may be more inclined to reach out to their communities during crises, but that shouldn’t be the only time. “Donors don’t want to be the ones always bailing out an organization because they don’t have a plan for sustainability,” Nathan says.

Build awareness about the great things you do, Nathan recommends. Luckily, marching arts groups can easily share their talents using just a smartphone and Facebook.

“Marching arts performing organizations have something that many organizations wish they had, and that is something that is perfect for video,” Cohen says. “It can be very powerful.”

In addition, band directors should lean on each other for support. The band or drum corps next door may be your biggest competitor, but the leader may also be your best source of advice. Hobart finds himself regularly relying on the support of his colleagues and sharing lessons he’s learned with them as well.

“As a director, you learn over the years as things come at you,” he says. “We’ll face an obstacle this year, and we’ll roll with it. Every corps does.”

Learn about bingo fundraisers here.